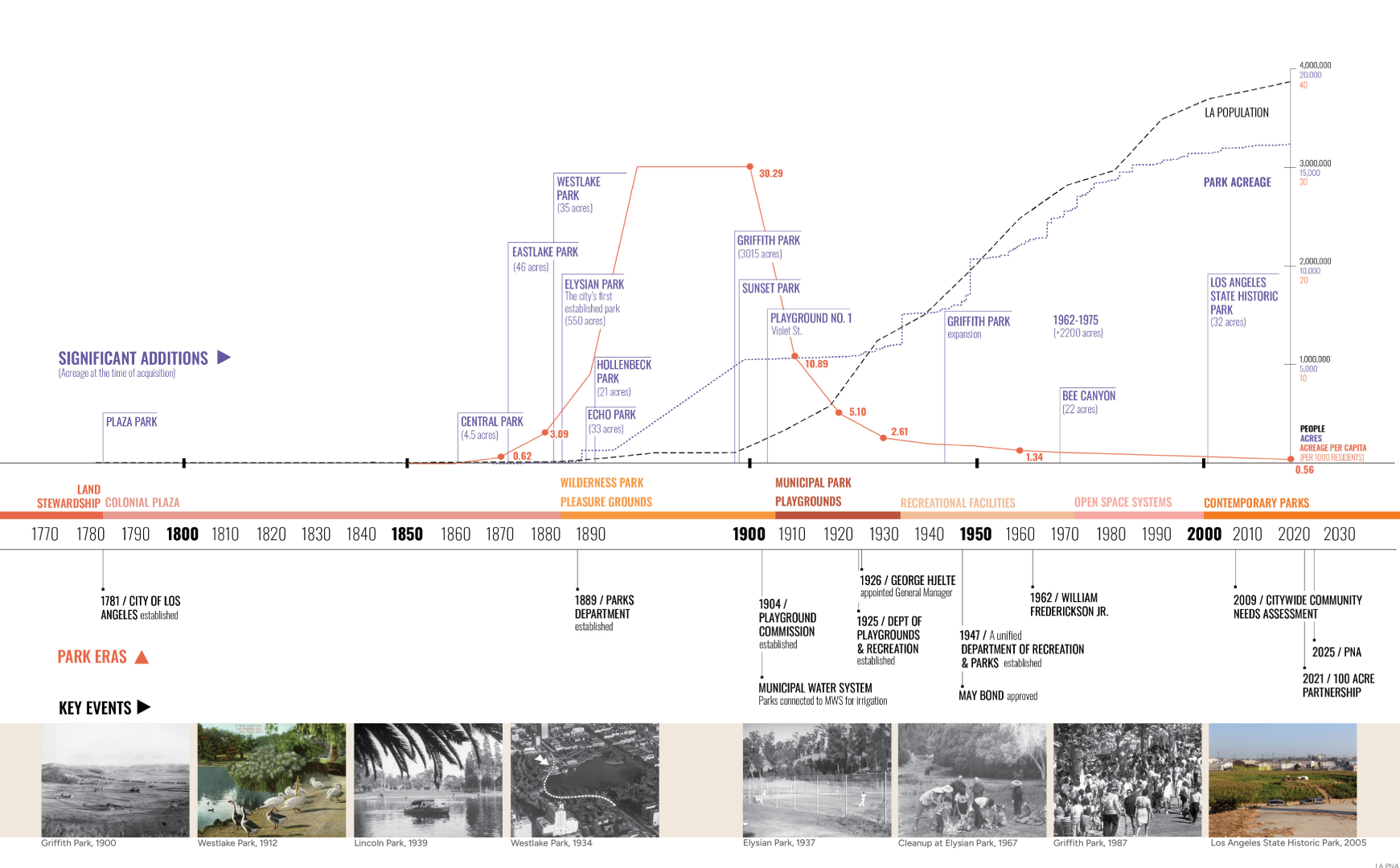

Understanding the history of the recreation and parks system in Los Angeles helps contextualize current conditions and provides an opportunity to look to the future to create a stronger system.

Los Angeles was initially envisioned as a garden city, prioritizing private open spaces and bungalows. This contrasted with the denser development model found in cities in the Northeast and Midwest of the United States. As a result, the development of public parks in Los Angeles has not always matched the City’s rapidly expanding population.1“Citywide Community Needs Assessment” (City of Los Angeles, Department of Recreation and Parks, 2009), 1. More recently, there has been a rapid densification and increase in the number of residents over the past fifteen years in the downtown area, whereas there are slower trends of expansion in the San Fernando Valley.2“Los Angeles Densest Urban Area: Revision of Census Bureau Data,” Newgeography.Com, accessed April 23, 2025. Findings from the Trust for Public Land show that Los Angeles has a relatively high abundance of large natural areas, but scores significantly low for amenities and overall equity and access.3“Gabrielino/Tongva Nation of the Greater Los Angeles Basin – NAHC Digital Atlas,” accessed March 28, 2025. Today, there is a collective effort to evaluate and reimagine how the parks system can better serve its residents in the future.

The following research is compiled primarily from the Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978 survey from the Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement, the 100 Years of Recreation and Parks report published by the Recreation and Parks Department in 1988, and news articles and historic photographs from the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Public Library.

City of Los Angeles Recreation and Parks Story

Land Stewardship (Pre-1781)

Los Angeles, known as “Tovangar” in the Tongva language, has been the home of Indigenous people such as the Tongva, or Gabrielino, Fernandeño Tataviam, and the Chumash for over 10,000 years.4“Gabrielino/Tongva Nation of the Greater Los Angeles Basin – NAHC Digital Atlas,” accessed March 28, 2025.

Indigenous groups have cared for and continue to shape the land that makes up the present day city of Los Angeles and its surrounding areas, extending from the Santa Monica Mountains to the Channel Islands.5“Gabrielino/Tongva Nation of the Greater Los Angeles Basin – NAHC Digital Atlas,” accessed March 28, 2025. Present-day downtown Los Angeles was primarily inhabited by the Tongva and their settlements were both independent and interconnected. In the 18th century, Spanish settlers established missions throughout California to spread Catholicism and strengthen allegiance to Spain, and many Indigenous communities were

enslaved at these missions. 6“Indigenous Peoples of the LA River Basin – LA River Master Plan,” accessed March 28, 2025.

Indigenous knowledge and present day research reveals that many present-day park sites are related to historic village sites or sacred sites of Indigenous Peoples. Spanish baptismal records collected by the Early California Cultural Atlas project suggest that there were around 100 Tongva villages spread across Los Angeles at the time of the missions.7Sean Greene and Thomas Curwen, “Mapping the Tongva Villages of L.A.’s Past,” www.latimes.com, May 9, 2019. Griffith Park was the former home of the Tongva and there are at least three known settlement sites within the park: near Fern Dell, west of Travel Town near Universal City, and close to the Feliz adobe and ranger station.8“Riots, Love Fests, Buried Secrets: Griffith Park’s Hidden Histories,” PBS SoCal, October 16, 2019.

In addition, Yaanga, believed to be one of the largest Tongva settlements, was located west of the Los Angeles River in the path of what is today Route 101, in close proximity to Elysian Park.80 The park is part of a belt of hilly land that was formerly covered with indigenous coast live oaks and California black walnut trees and provided sustenance and a reliable food source for the Tongva.9“The Origins of Elysian Park,” PBS SoCal, June 28, 2013.

In the San Fernando Valley, many park sites have ties to historic locations of Fenandeño Tataviam sites, such as Sepulveda Basin, which is near the site of the historic village Siutcanga. The name Siutcanga means “the Place of the Oaks,” and was established near a freshwater spring along the basin.10“Sepulveda Basin Vision Plan” (City of Los Angeles, June 2024). Present-day Sepulveda Basin recreation areas were part of the fishing, hunting, and gathering grounds of the inhabitants of Siutcanga.11“Sepulveda Basin Vision Plan” (City of Los Angeles, June 2024). The living descendants of the many Indigenous communities of Los Angeles continue to engage with the land through contemporary spiritual practices and climate activism.12“Indigenous Peoples of the LA River Basin – LA River Master Plan.”

The Early Years (1781-1885)

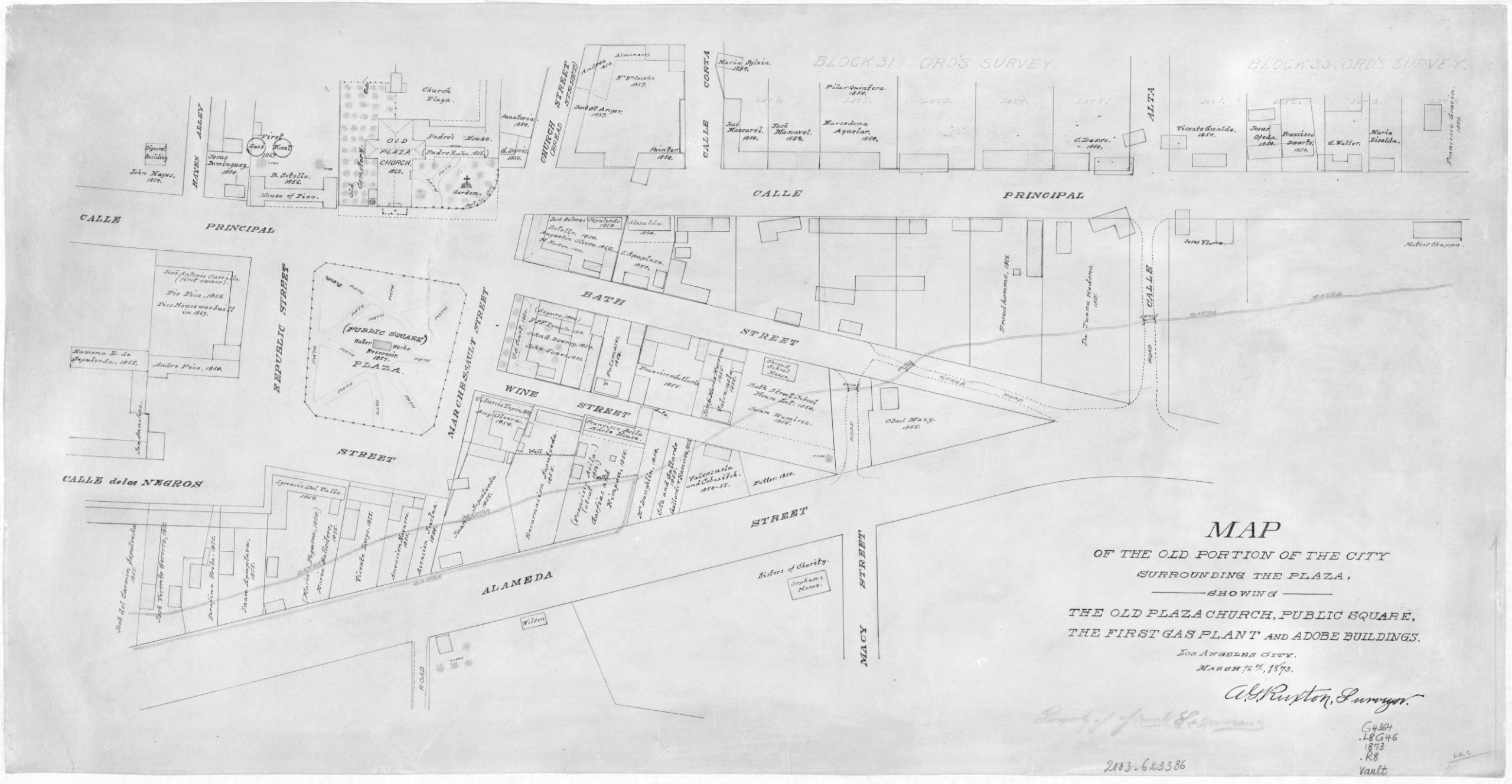

The City of Los Angeles was established by a group of settlers under Spanish colonial rule as a farming community in 1781.85 Under Anglo-American rule, which began in 1848, the City inherited two Spanish-style open plazas that structured public life: Plaza Park and Central Park (present-day Pershing Square).13“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement (City of Los Angeles,

Department of City Planning, Office of Historic Resources, December 2017), 6. These plazas were organized with formal lawns and fruit trees with eventual additions such as fountains and walkways as the surrounding neighborhoods developed more residential and commercial uses.14“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement (City of Los Angeles,

Department of City Planning, Office of Historic Resources, December 2017), 6. As the City’s population grew, it gradually began to acquire parcels of land to meet the needs of the residents for park purposes such as Eastlake Park (present-day Lincoln Park) which was acquired in 1874.15“Lincoln Park Boaters – Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection – Tessa: Photos and Digital Collections,” accessed March 31,

2025.

From Pleasure Grounds to Playgrounds (1886-1930)

As a result of growing land acquisitions, the City Council established the Parks Department in 1889.16“100 Years of Recreation and Parks” (Los Angeles: Los Angeles City: Recreation and Parks Department, 1988), 7. The largest park that came under their jurisdiction at the time was Elysian Park, which had already been acquired in 1886 and became the City’s first official park.17“100 Years of Recreation and Parks” (Los Angeles: Los Angeles City: Recreation and Parks Department, 1988), 7. A fifteen year period of expansion followed with the establishment of major parks such as Westlake (present-day MacArthur Park), Echo Park, Hollenbeck Park, Sunset Park (present-day Lafayette Park), and Griffith Park.18“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 8. These parks were primarily developed as pleasure gardens, which was in line with prevailing notions of nineteenth century romanticism and reflected the idea that there was innate goodness in a natural setting.19Galen Cranz, The Politics of Park Design: A History of Urban Parks in America (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982), pp. 3-59. Parks from this perspective were spaces of passive recreation and aesthetic beauty. Some parks also served as sites of water storage for the City’s zanja water distribution system prior to their integration with the municipal water system in 1904.20“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 9.

In parallel, parks like Griffith reflected the concept of the ‘wilderness park,’ a prevalent idea at the time that sought to recreate a sense of wilderness within the urban environment.”21“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 11.

This period was followed by a rise of municipal parks and playgrounds between 1904-1931, which were products of the Progressive Era reforms of the early 1900s.22“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 9. Both these park typologies pushed back on the concept of the passive pleasure ground. The municipal park was conceived to be an accessible setting for residents to engage in activities, containing sporting facilities such as ball fields, tennis courts, as well as structures for educational and cultural use. Concurrently, the playground emerged as a concept and was seen as a beneficial setting for children’s upbringing in underresourced neighborhoods.23Cranz, The Politics of Park Design, 62. Playgrounds were physically separated from parks and governed by a Playground Commission which was established in 1904 and supported by upper and middle-class women’s organizations.24“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 18. Family camps as a municipal recreation service were also established in 1913 and became popular programs which were replicated by other cities like San Diego and Sacramento.25“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 11.

The creation of a Department of Parks and a Department of Playgrounds and Recreation (formerly the Playground Commission) as a result of a new charter in 1925 was a turning point in the development of the City’s parks system.26“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 15. George Hjelte was appointed the first general manager of the Department of Playgrounds and Recreation in 1926 and continued in the role until 1962, playing a significant role in the evolution of the parks system. The concept of playgrounds expanded in the mid-1920s to include adult programming and recreation.27“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 22. The swimming pool, or plunge, as it was popularly referred to, was a key facility that characterized this shift. The plunge at the Griffith Park Playground was one of the largest swimming pools of the time and was opened to the public in 1927.28“Water Lures Many Weekly: Griffith Popular,” Los Angeles Times, August 21, 1927. In addition to swimming pools, municipal beaches were also constructed, and in 1928 the City used dredged sand to create Cabrillo Beach.

The Great Depression resulted in a reduction in budget for parks operations and employee salaries. As a response to the economic crisis, the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) established in 1933 allowed the City to hire unemployed workers for government programs. The City benefited from this program and was able to expand park maintenance and recreation programs.29“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 19. The concept of the recreational facility was growing in popularity among planners and landscape architects at this time and the Olmsted Brothers and Harland Bartholomew Associates proposed two types: the neighborhood center and the regional or district center.30“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 26. The neighborhood centers were envisioned as everyday recreational use spaces for all age groups; whereas, the regional centers would focus on athletic contests.

While their ideas were not fully realized due to economic constraints, elements were incorporated into WPA projects such as the Rancho Cienega Playground (present-day Rancho Cienega Park).31“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 28. Further, during the Second World War, parks and playgrounds were designated as places of refuge during an emergency, and recreation directors were involved in mobilizing volunteers in the Civil Defense Corps.32“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 21.

An improving economic climate and rapid population growth after the Second World War led to a reorganization of the parks system marked by the unification of the City’s separate park and playground bureaus into a single Department of Recreation and Parks (RAP).33“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 31. A bond of over $12.5 million was approved in 1947, which allowed for the expansion of park facilities. The concept of the recreational facility was fully realized and it was viewed as an essential public service that residents were entitled to. The bath house and club house were the two most common building types found in these early postwar recreation centers.34“City’s Recreation Projects Started,” Los Angeles Times, August 15, 1948. The City was interested in recreation as a means to combat “juvenile delinquency” and to develop “among Los Angeles’ more than 2,000,000 citizens stronger community and family ties.”35Robert E.G. Harris, “Los Angeles Enjoying a Boom in Recreation,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1950.

Late postwar recreational facilities in Los Angeles were characterized by a change in leadership, with William Frederickson Jr. taking over from Hjelte, and an increased budget. In 1957, a $39.5 million bond issue was approved, which was the largest bond issue ever voted by any city in the US until then for recreation.36“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 23. With an increase in automobile use, parking requirements were added to recreational facilities and a return to more traditional park styles was seen such as in Chatsworth Park (present-day Chatsworth Park North).37“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 38. There was also an expansion in postwar municipal golf courses, which were self-financing entities and relied on fees from players.38“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 42. The postwar years were thus characterized by economic growth and infrastructural expansion.

Following the period of postwar expansion, the City’s parks system declined, mirroring a nationwide trend. Hjelte’s retirement further symbolized the end of postwar optimism in the parks system.39“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 43. The movement of the middle class to the suburbs led to the rise of lower funded inner city parks and there were concerns of increasing violence and vandalism in the parks. In response, park rangers were granted limited peace officer status in 1989.40“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 44. This period of decline was also marked by economic constraints since the City was dependent on local property tax.41“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 23. Despite these challenges, several important milestones were achieved in this period, which included the adoption of the Quimby and dwelling unit construction tax that expanded funds for the development of additional parks and the development of the Griffith Park master plan.42“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 27.

THE MOVEMENT OF THE MIDDLE CLASS TO THE SUBURBS LED TO THE RISE OF LOWER FUNDED INNER CITY PARKS.

Following 1975, under James Hadaway’s direction, the parks system continued to oscillate between periods of growth and setbacks. The Department rolled out the vision statement “We Make L.A. a Better Place”, which was reflected in their expanded scope that included supporting cultural and social programs such as the “Just Say No” initiative to combat youth drug use and new facilities for residents with disabilities.43“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 29. 44“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 31. In 1996, Proposition K (Prop K), a 30-year funding initiative that prioritizes park development in underserved areas, was passed to help ensure that communities with limited access to green space received new recreational opportunities.45“Overview | Bureau of Engineering,” accessed April 7, 2025.

Since the 1970s, there has been a greater focus on equity, sustainability, and community engagement in RAP initiatives. Prop K has funded projects like the revitalization of MacArthur Park and the creation of Community School Parks, where school facilities are open to the public after hours.46“Community School Parks | City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks,” accessed April 7, 2025.

In 2008, the City began requiring certain departments, including the Department of Recreation and Parks, to pay reimbursements to the City’s General Fund for employee benefits, the Department of Water and Power for utilities, and the Bureau of Sanitation for refuse costs. These reimbursements have diminished RAP’s ability to meet and increase vital maintenance and recreational programming needs.47City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks, “Overview of the Adopted Fiscal Year 2023-2024 Department of

Recreation and Parks Operating Budget,”. Since the inception of these Department contributions in FY ‘08-09, over $960M has been diverted away from RAP’s core operations.48City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks, “Overview of the Adopted Fiscal Year 2023-2024 Department of

Recreation and Parks Operating Budget,”.

SINCE THE 1970S, THERE HAS BEEN A GREATER FOCUS ON EQUITY, SUSTAINABILITY, AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN RAP INITIATIVES.

In 2009, RAP conducted a Citywide Community Needs Assessment that provided a framework for long range planning initiatives but did not result in significant new funding. In 2018, RAP completed a Parks Condition Assessment that determined there was over $2B in unmet construction and maintenance needs.49City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks Planning, Maintenance and Construction Branch, Parks Condition

Assessment Report, 2018, 2. With the need for additional resources growing — and Proposition K, a 1996 voter-approved measure providing $25 million annually for recreation and parks through property taxes, set to expire in 2026 — the City developed a replacement funding measure.50“City of Los Angeles Proposition SP”, accessed April 25, 2025.

In November 2022, the Los Angeles City Council placed Proposition SP on the ballot, which aimed to generate approximately $227 million annually through parcel taxes.51“City of Los Angeles Proposition SP”, accessed April 25, 2025. However, this measure failed, which is attributed primarily to the lack of a clear, detailed plan for fund allocation.

The system today still faces ongoing issues with deferred maintenance, and reduced staff have made it difficult for RAP to achieve many goals in the 2000s. Nonetheless, since 2000, the park system has expanded by over 1,100 acres, including acquisitions such as South East Valley Skate Park, parks along the Los Angeles River and Aliso Creek Confluence Park, and Ascot Hills Park.

The current Park Needs Assessment is the City’s first significant initiative to strengthen the parks system since the 2009 Citywide Community Needs Assessment, reflecting the City’s initiative to meet the current and future recreational needs of the residents.

Sources

- 1“Citywide Community Needs Assessment” (City of Los Angeles, Department of Recreation and Parks, 2009), 1.

- 2“Los Angeles Densest Urban Area: Revision of Census Bureau Data,” Newgeography.Com, accessed April 23, 2025.

- 3“Gabrielino/Tongva Nation of the Greater Los Angeles Basin – NAHC Digital Atlas,” accessed March 28, 2025.

- 4“Gabrielino/Tongva Nation of the Greater Los Angeles Basin – NAHC Digital Atlas,” accessed March 28, 2025.

- 5“Gabrielino/Tongva Nation of the Greater Los Angeles Basin – NAHC Digital Atlas,” accessed March 28, 2025.

- 6“Indigenous Peoples of the LA River Basin – LA River Master Plan,” accessed March 28, 2025.

- 7Sean Greene and Thomas Curwen, “Mapping the Tongva Villages of L.A.’s Past,” www.latimes.com, May 9, 2019.

- 8“Riots, Love Fests, Buried Secrets: Griffith Park’s Hidden Histories,” PBS SoCal, October 16, 2019.

- 9“The Origins of Elysian Park,” PBS SoCal, June 28, 2013.

- 10“Sepulveda Basin Vision Plan” (City of Los Angeles, June 2024).

- 11“Sepulveda Basin Vision Plan” (City of Los Angeles, June 2024).

- 12“Indigenous Peoples of the LA River Basin – LA River Master Plan.”

- 13“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement (City of Los Angeles,

Department of City Planning, Office of Historic Resources, December 2017), 6. - 14“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement (City of Los Angeles,

Department of City Planning, Office of Historic Resources, December 2017), 6. - 15

- 16“100 Years of Recreation and Parks” (Los Angeles: Los Angeles City: Recreation and Parks Department, 1988), 7.

- 17“100 Years of Recreation and Parks” (Los Angeles: Los Angeles City: Recreation and Parks Department, 1988), 7.

- 18“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 8.

- 19Galen Cranz, The Politics of Park Design: A History of Urban Parks in America (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982), pp. 3-59.

- 20“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 9.

- 21“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 11.

- 22“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 9.

- 23Cranz, The Politics of Park Design, 62.

- 24“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 18.

- 25“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 11.

- 26“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 15.

- 27“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 22.

- 28“Water Lures Many Weekly: Griffith Popular,” Los Angeles Times, August 21, 1927.

- 29“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 19.

- 30“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 26.

- 31“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 28.

- 32“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 21.

- 33“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 31.

- 34“City’s Recreation Projects Started,” Los Angeles Times, August 15, 1948.

- 35Robert E.G. Harris, “Los Angeles Enjoying a Boom in Recreation,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1950.

- 36“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 23.

- 37“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 38.

- 38“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 42.

- 39“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 43.

- 40“Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978,” 44.

- 41“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 23.

- 42“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 27.

- 43“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 29.

- 44“100 Years of Recreation and Parks,” 31.

- 45“Overview | Bureau of Engineering,” accessed April 7, 2025.

- 46“Community School Parks | City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks,” accessed April 7, 2025.

- 47City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks, “Overview of the Adopted Fiscal Year 2023-2024 Department of

Recreation and Parks Operating Budget,”. - 48City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks, “Overview of the Adopted Fiscal Year 2023-2024 Department of

Recreation and Parks Operating Budget,”. - 49City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks Planning, Maintenance and Construction Branch, Parks Condition

Assessment Report, 2018, 2. - 50“City of Los Angeles Proposition SP”, accessed April 25, 2025.

- 51“City of Los Angeles Proposition SP”, accessed April 25, 2025.